Four different categories can be defined for a university’s working life cooperation. They consist of 14 different models. The categories are teaching, research, transfer of expertise and the level of administration. Among these, for example development projects, research projects and joint development of study content prepared by students in cooperation with the working life can be found. In addition, supplementary training, job exchange of personnel in the companies in the area, as well as the university’s fund raising, can be found in the models. The ones that are in the university’s official structures are more easily identifiable, but in general terms, it can be said that the most commonly used models in the Finnish university culture are the forms connected with teaching-led cooperation. (Jääskö, Korpela, Laaksonen, Pienonen, Davey & Meerman 2019)

When there is a desire to change the operating culture, the structures are changed first, but at the same time, efforts are made to impact the employees’ behaviour and motivation, as well as to guide the teachers toward the goals and the strategy. Jääskö et al (2019) mentions the teacher’s own motive and experience of benefits to his or her teaching work as the biggest motivating factor for engaging in working life cooperation. Lack of funding and time, on the other hand, are mentioned as barriers, but also contacts to working life. As Jääskö et al (2019) writes, changing the structures is not enough or immediately automatically increase working life cooperation. Instead, each teacher’s own willingness and interest in the matter, in other words motivation, is required.

More mistakes occur in working life projects than in fictitious examples that the students invented themselves during lessons.

This is natural, because the progress of the process is difficult to anticipate because of factors external to the project. However, mistakes should not be feared, because they occur also in the working life, and tolerance of uncertainty, fast changes and fixing issues are needed in it. Mistakes also teach students meticulousness. Indeed, Poijula (2018) reminds us that the working life learning taking place in a university provides an excellent opportunity and environment for practicing chaos, improving resilience, i.e., flexibility, and for developing the student’s ability to adapt, anticipate and change.

If, during a study module that includes a working life development project, the student’s courage, innovativeness, courage to bring up own opinions, and entrepreneurship, are evaluated and errors are not given penalties for, in the best case, something new and different can be created. The young have their own perspective and great ideas, when they are encouraged to share them. Pakkala, Väänänen, Brauer, Karapalo, Virkki-Hatakka & Kettunen (2019) mention that what is important in working life projects is that a student learns from the peers and together with and from others, as well as collegiality.

Working life cooperation projects are one of the best ways, not only to maintain one’s own current topic expertise but also to strengthen the position and image of Vaasa University of Applied Sciences as a competent actor, and to provide all parties with an opportunity to benefit from the development projects.

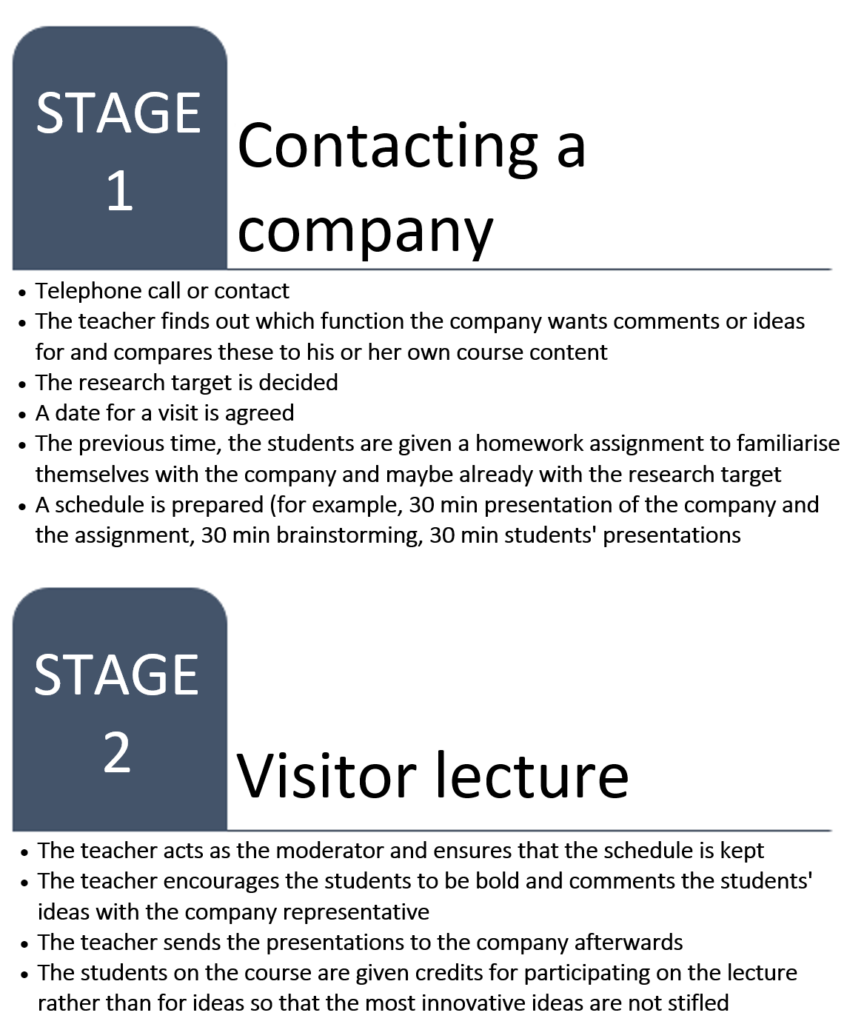

As Jääskö et al (2019) mentions, the lack of teachers’ contacts with the working life is one of the factors that hinder business life cooperation. This can, of course, be influenced from the higher levels of the school by organising meetings between teachers and companies, as has been done at Vaasa University of Applied Sciences already for years. Other network development will then rest on the teacher’s own persona, activity and use of time. In a university teacher, networking is something that will bear fruit in the future. Growing your own network can be started at any time, it is never too late. Making expertise visible helps in building a network, and this is something worth doing at least in the social media channels, for example on the LinkedIn platform. If getting a project for the entire course seems like a big effort, it is possible to test the so-called Speed dating model, which lowers both parties’ thresholds for cooperation. The concept lasts for a few hours. Because these days, many university study modules have a visiting lecturer who presents his or her company, Speed dating is a more developed version of this in which all three parties benefit: the company, the teacher and the students. In the concept, the teacher makes contact with the company and asks the company to present itself during his or her lecture. After this, a question or an assignment is defined for which the company hopes to receive the students’ comments and ideas. As homework, the students familiarise themselves with the company. The visit itself includes a presentation of the company and the assignment, brainstorming sessions, and presentation of the results. Sometimes, the first, most intuitive idea is the best. Sometimes, a long process can extinguish even the most innovative of ideas. In this way, the cooperation has already got off to a start and in future, research projects can be developed.

Everyone that gets involved in these kinds of projects wants to give the students a chance to learn the skills needed in working life, as well as project work. Nobody knows in advance whether the project achieves what is hoped for. There is, of course, many kinds of success, but at the project’s definition stage, it is a good idea to remind the representative of working life that the intention is also to give the students responsibility for leading their own projects and being responsible for the end result. The responsibility for bringing ideas and the responsibility to process information. The teachers draws the framework, the students are responsible for ideas and outputs. According to experience, a project implemented for working life in which the students themselves are allowed to be the leaders of the projects, gives the student group a higher motivation for studying than a fictitious course assignment, and therefore better learning results.

In the last decade, I have implemented about 30 larger projects during study modules for companies in the Vaasa region. With the students, a social media plan has been prepared for a company called Beibamboo selling organic baby clothes, a trade fair organiser’s handbook for Pohjanmaan Expo, an image study for OK Perintä, a customer event for I-Mediat, a marketing plan for a game company called Platonic Partnership, and a study concerning thought management for Wärtsilä. From each one, something is learned. Sometimes, the lesson has been what definitely should not be done next time.

Working life cooperation has come to universities to stay, and it should concern every teacher responsible for study modules. Motivation starts with each person him-or herself, as well as with the ability to step outside one’s own comfort zone. One can only develop by trying things, learning something new and by giving oneself a chance. For better or worse.

10 theses for leaders of working life projects:

- Get boldly involved. Pick up the telephone and make a call. Browse the LinkedIn platform. Think about who you already know. Sell the idea and the enthusiasm of the students

- Remind the customer that this is also, above all, an opportunity to develop the skills and experiences that the students will need in working life.

- Define the project’s objective in advance and sufficiently well with the working life representative, also the so-called soft skills that the students should recognise having learnt.

- Remind the students that they are responsible to the customer for the result

- Give responsibility also to the students, do not plan every stage of the project too precisely but give them a chance to also learn project management.

- Specify the research target sufficiently to leave time for theory, project learning and reflection.

- Organise time on the course for learning working life skills (presentation skills, problem-solving skills, critical thinking, creativity, emotional intelligence, social skills)

- Let the students make mistakes and let them learn from their mistakes

- Encourage all kinds of ideas. Reward the most amount of ideas and the craziest ideas

- Call a friend. In other words, ask a colleague for help. There is always someone that you can bounce some ideas around with

- Encourage peer feedback

Motivate! Praise! Be there in support!