FFive IT students, Daria Zakharova, Yevhenii Nazarov, Stanislav Ostapchuk, Dat Phi and Nguyen Nguyen, spent their holiday months doing something that did not just look like software work; it was real software work. Together with teachers Anna-Kaisa Saari and Lotta Saarikoski they joined the TETRA project, a spin-off from VAMK’s “PK-yritysten TKI-Polku” -initiative. Their goal was ambitious but clear: create an interactive training and learning platform that companies could actually use for onboarding and internal training.

This article opens the series by looking at the project from the student team’s perspective: what they learned, how they worked and why this summer was different from a typical school course.

Not just a course project

What made the project different from normal course work was the setup. Instead of doing an isolated assignment, students worked in a way that emulated real software development. They created branches, opened merge requests, reviewed each other’s code, resolved merge conflicts and ran everything through a CI/CD pipeline. The team had automated deployment, meaning that when a change was approved, it was automatically pushed to the server. It wasn’t just development; it involved documenting the process and the environment precisely. That rhythm, combined with the knowledge that real organizations might use the application, made the work meaningful. It did not feel like a school exercise but like a small commercial project with real expectations.

The topic itself was motivating. We all know that onboarding and training can often be formal and boring. The group wanted to build something that would make that experience more engaging, playful and easier to repeat. Knowing that the platform could bring value to companies helped the team stay focused during the summer. It is easier to fix bugs at 15:30 on a hot July day when you know someone will click that button later.

Rotating roles and learning the whole stack

In the project, the team avoided locking people into fixed roles. Instead, responsibilities were rotated based on what each person wanted to learn. During the summer, everyone tried frontend, backend, styling, database configuration, planning, documentation and deployment. Most team members also acted as a Scrum master for at least one sprint. This role provided experience in prioritizing and planning, but also in listening to others and keeping the team aligned.

Rotation of the roles also prevented the classic situation where one student is always “the React person” and another is always “the database person.” It also made the whole team more resilient. If someone was away, another person could pick up their task because all had seen the codebase from different angles. This approach also improved teamwork and communication skills; students learned to communicate openly, avoid conflicts, distribute tasks fairly, and ask for help early instead of struggling alone.

Everyday rhythm

Each day followed a clear cadence. Every weekday started with a daily meeting at 10:00 on Discord. In that short check-in, progress was discussed, priorities clarified, and possible blockers identified. After the daily, everyone focused on their tasks, created a branch, and worked toward a merge request, typically completing one to three tasks per day. The routine was simple, but it brought a necessary structure to the summer.

During the day each other’s merge requests were reviewed, comments given, clarifications asked and small things were fixed. The rule was simple: if you saw a problem, mention it right away. For design and feature decisions, team shared quick mockups and proposals to avoid waiting for formal meetings. Over time these small routines turned into a natural way of working together.

Communication in the project

Communication in the project was mostly online and quite lightweight. Students and teachers had common Discord server for dailies and common updates. For students internal discussion they preferred Telegram group. The mix of structured and informal channels worked surprisingly well, because there was no need to spend time wondering where to write something, everyone knew where to go.

Every two weeks students had a longer meeting with the teachers. In these sessions they demonstrated the current progress, usually by running the app locally and walking through the features they had added. Teachers gave feedback on design choices, helped in prioritizing between “must-have” and “nice-to-have” features, and guided with technical decisions. These follow-ups also gave a chance to reflect on the teamwork, share the learning outcomes, and ensure that the direction matched the project’s goals.

And it was not only work: sharing cultural insights, travel ideas, and occasional ice cream made the project feel less like a task and more like a shared experience.

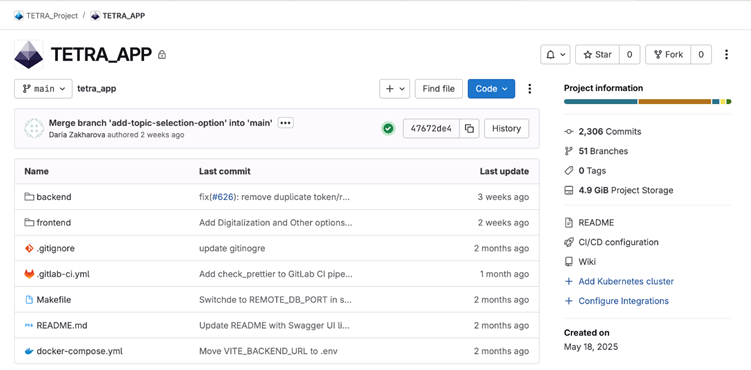

GitLab: The Backbone of the Project

GitLab was the team’s central workspace. It was where the code was stored, tasks were planned, each other’s changes were reviewed and CI/CD pipeline ran to deploy updates. In practice, GitLab, shown in Figure 1, was the backbone of the project. Figure 1 shows that 2306 commits were done during the summer with 51 branches, which gives an idea of how much was actually done.

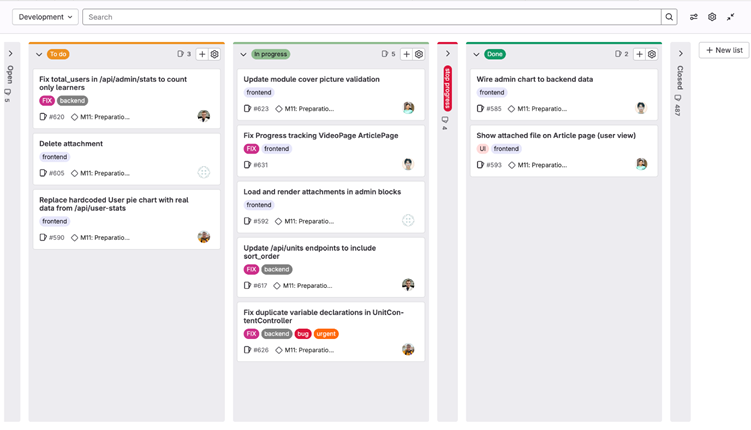

GitLab’s issue board, shown in figure 2, was used to create and assign tasks. Issues were labelled, given deadlines, and moved across stages (in progress -> done -> waiting for approval). Everyone worked in their own branch and no one merged their own code. Each merge request needed at least one other person to approve it, often two. That rule made code reviews a part of learning, not a formality. Reading other people’s code helped everyone understand the architecture better and write clearer code themselves. The team agreed some principles and also documented them as follows:

- only change code that is part of your task

- create a new ticket if you spot something else

- never approve your own merge request.

These small rules kept the repository clean and professional, and exactly as many software teams work in real life.

Technical growth in one summer

Technically, the project offered deep learning opportunities. Students sharpened their React skills, particularly with contexts and state management. They got to set up Docker and CI/CD pipelines from scratch. Using Java on the backend helped them understand the full stack and how different parts of a system interact.

Students also learned, maybe for the first time properly, why version control discipline matters. When five people work in the same codebase every day, naming conventions, branching strategies and documentation practices aren’t just details; instead, they are the difference between smooth progress and hours spent resolving conflicts. This is the kind of learning that is hard to get from lectures alone.

The proudest moments came when the app was deployed, and the team could finally click through it as a working product. After hours of fighting bugs, seeing everything run smoothly gave a real sense of achievement. For many, it was the first time they felt: we can really ship something.

Tips for the next team

If we had to give advice to the next student team doing a similar summer project, it would be the following. First, agree on your communication rules early. Decide which channel is for daily updates, when to meet, how you name branches and how you write issues. It removes confusion later and saves energy for the actual work.

Second, treat code reviews as learning, not checking. Ask questions, explain your decisions and read your teammates comments. A good review makes the code better, but it also makes the developer better.

And as last, respect your team. Communicate openly and honestly, ask for help, learn from others and share the knowledge you’ve acquired. Projects end, but the way you treat people and the skills you build together stay with you.

As a conclusion

This was only the first summer of TETRA. We all hope the platform will still evolve and the content will grow, but we can already say that working in a real project, with real practices and real expectations, is one of the fastest ways to learn software development. It showed how much can happen when a small team focuses on something meaningful for a few months. And it is much more fun than doing it alone!

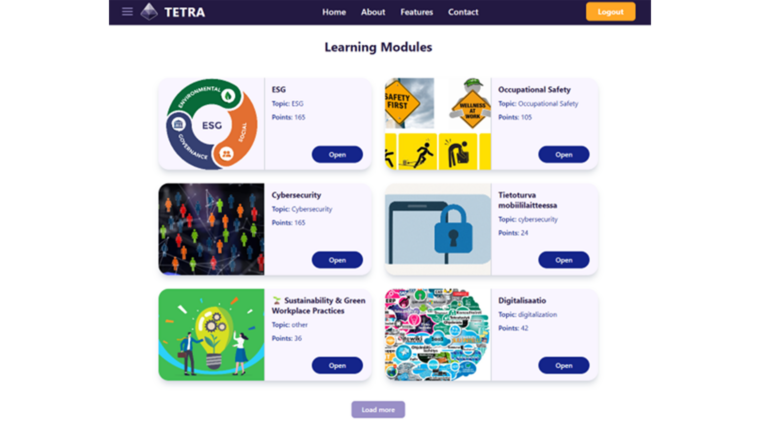

Now that we’ve met the team and understood their way of working, let’s shift focus to what they actually built. In the next article, we will explore the TETRA application itself, from the gamified learner journey to the admin tools that power it.RA application itself, from the gamified learner journey to the admin tools that power it.

This text has been produced as part of the project “RDI Path for SMEs” (1 Jan 2024–31 Dec 2025) coordinated by Vaasa University of Applied Sciences. The project is funded by the ELY Centre and aims to promote the growth of RDI activities of SMEs in the West Coast region and their cooperation with regional RDI actors. The project seeks to strengthen companies’ capabilities for developing innovations, internationalization and sustainable growth through multidisciplinary education, development activities and networked collaboration. The project is implemented in cooperation between Vaasa University of Applied Sciences, Centria University of Applied Sciences and Turku University of Applied Sciences.