For the TETRA team, this wasn’t an option. They were building a platform designed to last for years, with new teams picking up the baton each summer. To make this possible, they needed more than just clean code; they needed a map for the future.

In this final article of the series, we explore the “boring” superhero of software development: Documentation. We look at how the team used modern tools to ensure that the next developer doesn’t have to guess how the system works.

Software documentation

In a fast-paced agile project documentation is often the first thing to be cut. Developers often imply that the code documents itself. However, six months later even the original author might not remember why a specific function exists. Software documentation is a fundamental element in ensuring the quality and resilience of complex information systems. In the context of distributed teams and iterative development methodologies, such as Agile and CI/CD, structured documentation serves as a tool to minimize risks related to requirement inconsistencies, integration errors, and knowledge loss during team member transitions.

For TETRA documentation was a survival strategy rather than an afterthought. With a distributed team and rotating roles, writing things down was the only way to keep everyone aligned. The team adopted a layered approach that began at the code level where tools generated documentation automatically from the source. Above that the architecture level provided visual diagrams and high-level descriptions in the Wiki. Finally the process level offered guides on how to work styled as rules of the road.

Self-Documenting Code: Swagger and TSDoc

The team did not want to write separate Word documents that would get outdated instantly. Instead they integrated documentation directly into the development workflow.

Server-Side: Swagger (OpenAPI)

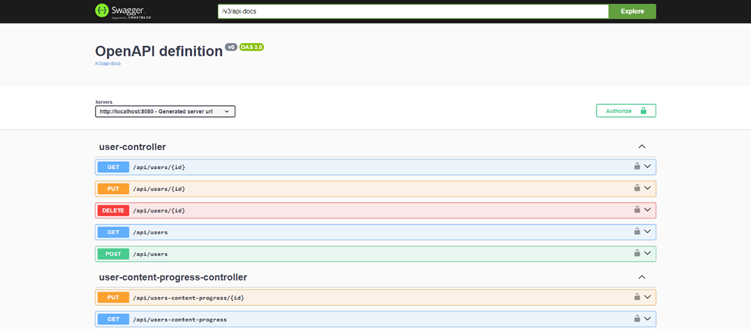

For the Java Spring Boot backend the team used Swagger to automatically scan the code and generate a live and interactive website describing every API endpoint. Swagger provides a standardized OpenAPI format for describing endpoints, including input parameters, data formats, response codes, and potential errors. This meant that when a frontend developer needed to know how to fetch user progress they did not have to message the backend developer. Instead they just checked Swagger to see the endpoint and could even test it right in the browser. This resulted in fewer interruptions and faster integration. Figure 1 shows a general Swagger overview of the project API’s.

Client-Side: TSDoc

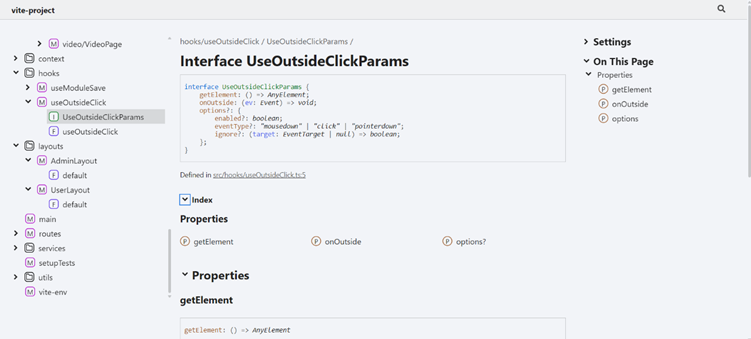

The client-side application, implemented with React and TypeScript, was documented using TSDoc. This tool allowed the creation of structured comments directly in the code, describing component interfaces, their input and output data, as well as business logic. TSDoc improved code readability and maintainability, which is particularly important in Agile environments characterized by frequent requirement changes. Code-level documentation accelerated onboarding for new developers, reducing their reliance on informal communication channels such as messaging discussions.

Combined with Swagger, TSDoc created a coherent documentation chain covering both server-side and client-side aspects of the system. Figure 2 shows TSdoc generated documentation from frontend class

GitLab Wiki

While Swagger handles the technical details the GitLab Wiki handles the reasoning behind them. This is where the team documented the broader context that code comments cannot capture.

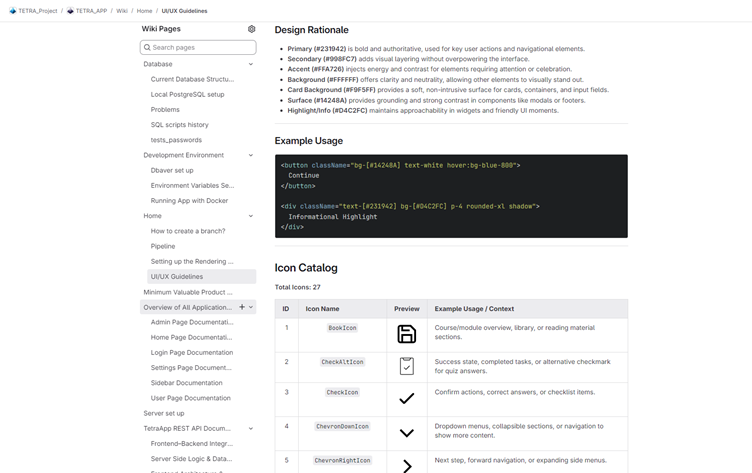

The Wiki became the project encyclopedia. It contained architecture overviews detailing how containers talk to each other alongside visual Entity-Relationship Diagrams showing how database tables link together. It also hosted the UI/UX guidelines that defined the project color palette and icon usage. By linking every Merge Request to a relevant Wiki page the team ensured that documentation evolved alongside the code. This approach reduced review time, improved code quality, and minimized the risk of inconsistent changes. The Wiki served as a bridge between formal technical documentation and high-level system descriptions, creating a unified information space for all participants.

Special attention was given to documenting database architecture and infrastructure components. All changes to the database structure were recorded using entity-relationship diagrams (ERDs), providing a visual representation of the current schema and its evolution. SQL scripts were accompanied by a change history, stored in a version-journal-like format, allowing tracking of modifications and their rationale. Similarly, configurations of remote servers and DevOps pipelines, including deployment and build scripts, were documented. Such detailed documentation ensured reproducibility of infrastructure processes and reduced risks associated with knowledge loss during personnel changes. For instance, in cases where tasks needed to be transferred to a new developer, the documentation allowed rapid context recovery without significant time expenditure. One example is the UI/UX guidelines, as shown in Figure3, that provided clear guidance to developers, how to follow the agreed styling.

Benefits of documentation

The layered approach to documentation, implemented using Swagger, TSDoc, GitLab Wiki, and specialized database and DevOps descriptions, proved highly effective in the context of developing complex software systems. Formalizing APIs and client logic, providing contextual descriptions in the Wiki, and thoroughly recording infrastructure components ensured transparency, reproducibility, and process resilience. This approach is recommended for projects employing iterative methodologies and requiring a high degree of coordination among distributed teams.

Conclusion: From Summer Job to Professional Product

The true value of this documentation will be seen next year when a new group of students opens the repository. Instead of spending four weeks deciphering difficult code they will find a Wiki that welcomes them and explains the architecture. They will have access to a Swagger page that lets them test the backend immediately and they will work with code that explains itself through clear typing and comments. This turns a summer project into a continuous product development lifecycle.

This series has taken us on a journey through the TETRA project. Part 1 introduced the student team and their professional way of working while Part 2 showed us the gamified application they built. Part 3 revealed the modern and containerized architecture under the hood and this final part demonstrated how they future-proofed the project with documentation.st exercises. With the right tools and the right attitude combined with a commitment to quality a small team can build software that is robust, scalable and ready for the real world.

This text has been produced as part of the project “RDI Path for SMEs” (1 Jan 2024–31 Dec 2025) coordinated by Vaasa University of Applied Sciences. The project is funded by the ELY Centre and aims to promote the growth of RDI activities of SMEs in the West Coast region and their cooperation with regional RDI actors. The project seeks to strengthen companies’ capabilities for developing innovations, internationalization and sustainable growth through multidisciplinary education, development activities and networked collaboration. The project is implemented in cooperation between Vaasa University of Applied Sciences, Centria University of Applied Sciences and Turku University of Applied Sciences.