In the previous articles, we met the team and explored the gamified learning features of TETRA. Now, we look under the hood. We explore how a modern web client, a robust backend, and an automated DevOps pipeline come together to create a system that is stable, scalable, and secure.

This wasn’t just about writing code; it was about making hard architectural choices, including a pivotal decision to break the system apart when the “easy way” stopped working.

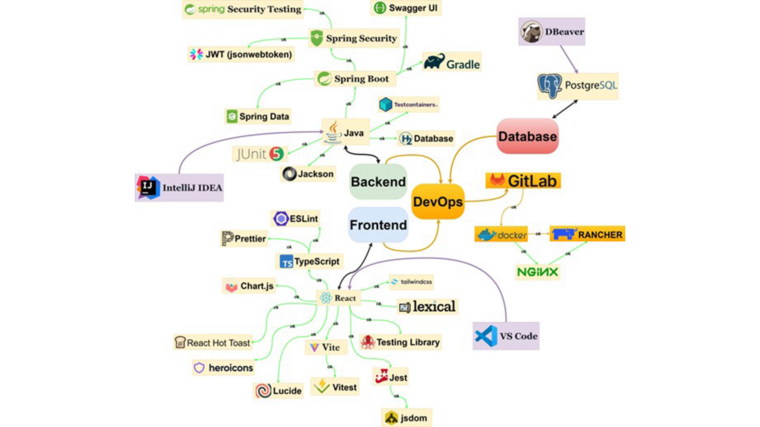

The Big Picture: Three logical layers

From the beginning, the goal was to avoid “spaghetti code.” The team built TETRA as a modern web application with a clear separation into three key logical layers: the client subsystem (Frontend), the server subsystem (Backend), and the infrastructure-operational subsystem (DevOps):

- Frontend (The Face): A React/TypeScript application that runs in the user’s browser. It handles everything the user sees and interacts with, from drag-and-drop interfaces to video playback.

- Backend (The Brain): A Spring Boot service that handles rules, security, and data. It sits safely behind the scenes, processing requests and ensuring that only authorized users can access sensitive information.

- Infrastructure (The Foundation): A DevOps layer based on GitLab, Docker, and Kubernetes that keeps everything running. This layer automates the deployment process, meaning new features go live without manual server configurations.

The result is a clean separation. The frontend doesn’t care how the database is structured, and the backend doesn’t care what color the buttons are. This separation allows the interface to evolve rapidly without risking the integrity of the data.

The Frontend layer: Smooth, “App-Like” feel

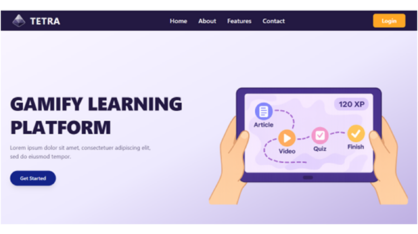

The client is a Single-Page Application (SPA) built with React and TypeScript. Unlike older websites that reload the page every time you click a link, TETRA loads once and then updates instantly. This creates a smooth experience, crucial for mobile users learning on the go.

To keep things secure, the frontend uses Protected Routes. When a user tries to access an Admin page, the frontend checks their digital key (JSON Web Token). If they don’t have the right clearance, the door remains locked, the user is redirected to the login page or shown an access denied message. This pattern makes it clear where access control happens and keeps the logic in one place.

On top of the core stack the team used Tailwind CSS to structure layout and styling. They also used Chart.js for admin dashboard visualisations, Vitest + Testing Library for component tests, and ESLint/Prettier to keep the codebase consistent. Tailwind’s utility classes helped them build responsive layouts quickly without maintaining a large custom CSS codebase. The aim was not to create a visual design showcase but to make the application look and behave like a production app rather than a quick school prototype. An example of the frontend in one course is shown in Figure 1.

The Backend layer: The enforcer of Rules

While the frontend makes things look good, the Spring Boot backend ensures they are good. It exposes a REST API that the frontend talks to. The backend is where the “Business Logic” lives. For example, a rule like “A module cannot be published if it is empty” is enforced here. Even if a hacker tried to bypass the frontend buttons, the backend would reject the request.

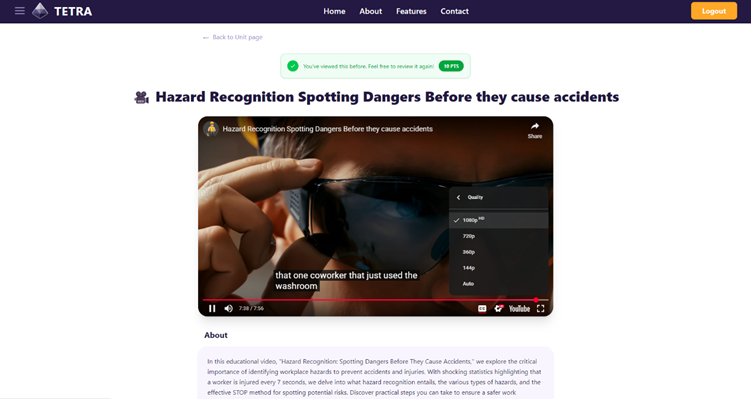

All data lives in a PostgreSQL database. The schema is kept intentionally simple, defining tables for modules, units, content blocks, users, roles and progress data. Modules describe the higher-level training packages, units define the building blocks inside them and content blocks represent individual videos, articles or quizzes. User progress is stored as links between users and completed content, with timestamps and points.

The backend code maps this schema to Java entities and repositories and uses them to implement the REST endpoints. For example, there are endpoints to list available modules for a given user, to fetch the structure of a module, to submit quiz answers and to update completion status. This means that all business rules, such as the order of content, gating of units or awarding of points, are implemented once in the backend and kept correct even if the frontend is later replaced or modified. Figure 2 shows a simplified database schema that underpins these operations.

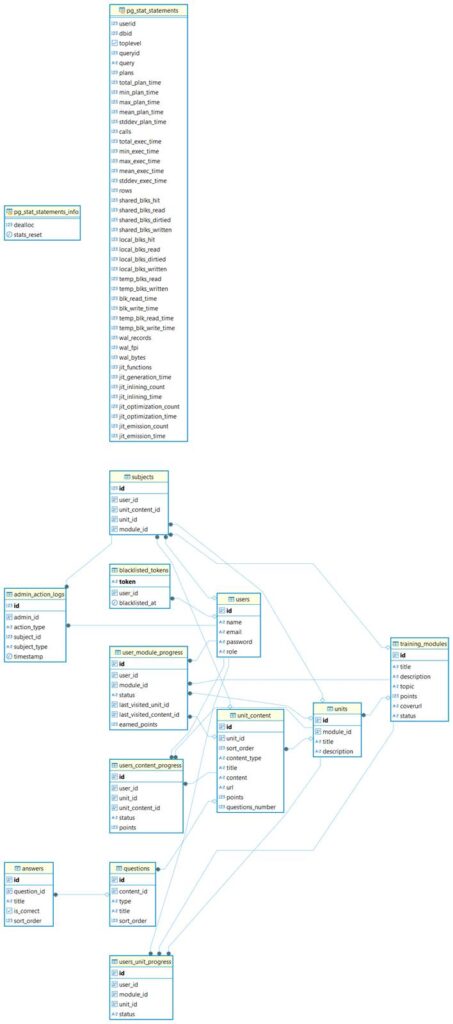

The DevOps layer: GitLab CI/CD, Docker and Kubernetes

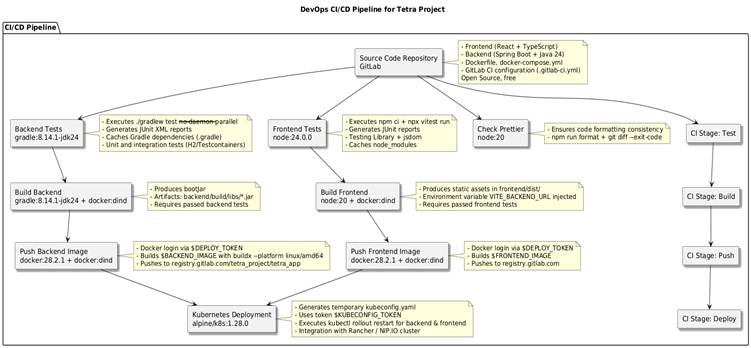

One of the project’s most significant achievements was the implementation of a fully automated CI/CD (Continuous Integration / Continuous Deployment) pipeline. In traditional student projects, deployment is often a manual, error-prone process of copying files to a server. For TETRA, the team built a pipeline in GitLab that acts as an automated assembly line, ensuring consistency and quality with every single update.

Every time developer merges code into the main branch in GitLab, the CI/CD pipeline starts its process. First, it runs a battery of automated tests to ensure the new changes haven’t broken existing functionality. Once the tests pass, the system builds fresh Docker containers for both the frontend and backend, packaging the application into portable, self-contained units. These images are then pushed to a digital registry and finally deployed to a Kubernetes cluster that runs the live application.

This automation solves the infamous “it works on my machine” problem. By using Docker and standardizing the deployment process, the team ensured that the application runs exactly the same way in the cloud as it does on a developer’s laptop. Furthermore, critical secrets, such as database passwords and API keys, are stored as masked variables within GitLab, meaning they are injected securely during deployment and never exposed in the source code. This level of automation allows the team to focus on building features rather than fighting with servers.

The overall CI/CD process is illustrated in Figure 3.

The Turning Point: The “Monolith” Problem

Early in the summer, the team faced a major architectural dilemma. To keep things simple, they initially tried to package the entire application, frontend and backend, into a single container (a “Monolith”). Pretty soon it became a nightmare to manage. The frontend’s routing logic conflicted with the backend’s API endpoints. Every time they wanted to fix a typo in the UI, they had to rebuild the entire server application.

As a solution, the team decided to split the application into two separate containers: one for the API and one for the UI, connected by Nginx. This provided two benefits. First, independent scaling. If the UI gets heavy traffic, it can be scaled up without touching the database layer. And secondly, faster development. Frontend developers could deploy updates in seconds without waiting for the heavy Java backend to rebuild.

This trade-off, accepting more complexity in deployment to gain flexibility in development, is a classic real-world architectural decision.

Testing strategy: quality built-in, not added on

Testing wasn’t treated as an afterthought or a manual checkbox at the end of the project. Instead, the team integrated automated quality checks directly into the CI/CD pipeline. Given the time constraints of a summer project, the goal wasn’t 100% coverage but rather “smart coverage”, verifying the critical paths that would break the application if they failed.

On the backend, the team employed a tiered approach. Simple business logic was verified with fast unit tests, while more complex operations, like creating a module or publishing content, were validated using integration tests. To make these tests realistic, the team used Testcontainers to spin up actual Dockerized services (like the database) during the test run. This ensured that when the code said “save to database,” it actually worked in a real environment, not just in a mock simulation.

Frontend quality was equally rigorous. Using Vitest and Testing Library, the team simulated user interactions: clicking buttons, navigating routes, and submitting quizzes, within a lightweight jsdom environment. This allowed them to verify that the UI behaved correctly without the overhead of launching a full web browser for every test. Additionally, code style consistency was enforced automatically; if a developer tried to push code that didn’t match the project’s formatting rules, the pipeline would reject it immediately.

While the current suite focuses on unit and integration testing, the architecture is designed to support growth. The pipeline is ready for future teams to plug in end-to-end (E2E) testing tools like Playwright or Cypress, ensuring that as the feature set grows, the safety net grows with it.

As a conclusion

TETRA is not tied to a single laptop or classroom setup. It is a complete example of how modern systems are built: a React SPA talking to a Spring Boot backend, a PostgreSQL database storing the content and progress, and a DevOps chain that turns code into running containers in a cluster. The user interface can be maintained by one team, the API by another and operations by a third, if needed. At the same time the whole system is compact enough to be understandable for a student team within one summer.

For the students, this architecture was the ultimate learning environment. They learned that code is important, but structure is what makes a project survive. For companies, TETRA shows that student projects can reach a level where they are not just exercises but realistic prototypes that can be continued and integrated into everyday use.

But how do we ensure that the next team of students understands this structure? In the fourth and final article of this series, we will discuss the Documentation strategy that enables the continuity for the project.the Documentation strategy that enables the continuity for the project.

This text has been produced as part of the project “RDI Path for SMEs” (1 Jan 2024–31 Dec 2025) coordinated by Vaasa University of Applied Sciences. The project is funded by the ELY Centre and aims to promote the growth of RDI activities of SMEs in the West Coast region and their cooperation with regional RDI actors. The project seeks to strengthen companies’ capabilities for developing innovations, internationalization and sustainable growth through multidisciplinary education, development activities and networked collaboration. The project is implemented in cooperation between Vaasa University of Applied Sciences, Centria University of Applied Sciences and Turku University of Applied Sciences.